Unmatched in the world: Ukraine has created a unique demining market

Military operations have turned a large part of Ukrainian land into minefields, threatening not only the lives of civilians but also paralyzing the economies of these areas by preventing the restoration of agriculture, industry, and infrastructure.

During the year, the area affected by the hostilities reduced to 138,500 square kilometres. And since September 2024, the government has launched a humanitarian demining programme compensating farmers for the cost of demining agricultural land from the state budget.

Learn how Ukraine launched its new humanitarian demining market, how the compensation mechanism for farmers works, and how international partners support Ukraine in this effort – in this collaborative feature by LIGA.net and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Ukraine.

The process of humanitarian demining

Humanitarian demining is carried out in all regions where hostilities took place and in settlements that were under Russian occupation. This process consists of three main stages: a non-technical survey of the territory, a technical survey, and clearing the area of explosive ordnance. The work is carried out by certified mine action operators.

"Non-technical surveys are mainly necessary to see if there is any evidence of the presence of explosive ordnance and to separate safe areas from dangerous ones," explains UNDP Mine Action Specialist Oleksandr Lobov.

This is done by collecting and processing information from key informants, such as local authorities, residents, and the military.

The next stage is a technical survey. Using equipment, specialists make passes through the territory until they find unexploded ordnance.

"If a mine is found, there is a high probability that there is a minefield there, because there is never just one mine," Lobov explains. "As a rule, they are placed according to a certain pattern. Then, they search for other mines within a 50-meter radius to determine the minefield pattern. When we know that the area is confirmed to be contaminated, we proceed to clear it."

The speed of mine-clearing depends on many factors: the type of terrain on the territory, the density of any vegetation present, and the level of contamination of the area with explosive objects. It also depends on the method of demining employed.

During humanitarian demining operations, the mine-clearing approach is selected on the basis of "a set of tools and means" designed for these purposes. The approaches usually employed are manual demining, mine-sniffing dogs, and mechanized demining systems. With the development of artificial intelligence and related technologies, innovative solutions such as drones for remote detection of explosive ordnance and specialized algorithms for data analysis and risk prediction have been added to this list.

Depending on the terrain type and level of contamination, one method or a combination of methods is used. Mechanical and manual systems have been found to be the most effective way to clear agricultural land.

Mine-sniffing dogs are also very effective in this work. Although they cannot replace manual demining, they are a powerful tool when used in combination with manual and mechanical demining.

"During manual demining, a deminer checks the ground with a mine detector and a probe," Lobov says. "During the day, they can clear between three to 20 square meters. Under such conditions, it would take a sapper several years to clear a hectare, or 10,000 square meters. Mine-sniffing dogs are not the main tool for humanitarian demining, but in some cases – taking into account the terrain, vegetation, and type of contamination – their use can significantly speed up the process. Sometimes it can be several or even ten times more effective."

This year, with financial support from the Netherlands and Spain, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), together with the Ministry of Economy of Ukraine and international organizations MAG and APOPO, launched a large-scale humanitarian demining project using dogs. The initiative involves 16 specially trained dogs and eight dog handlers, who speed up the clearance of areas due to their ability to detect explosives much more quickly than traditional methods. A national standard for demining using dogs is being developed to systematize and improve this area.

Internal and external quality control are carried out on completion of mine-clearing work, and a certificate is issued. The internal control is carried out by the operator who demined, and the external control is carried out by the Mine Action Centre (MAC). According to the standards, the minimum inspection depth is 15 cm. About 10% of the cleared territory is checked in different areas.

"The inspection is a very serious issue," Lobov says. "Of course, the responsibility lies primarily with the operator who conducted the humanitarian demining, but the organization that carried out quality control also has some responsibility. And, of course, there is the state, which sets certain quality criteria and provides the kind of control and monitoring we have. It’s a shared responsibility."

Formation of the humanitarian demining market

Ukraine formed a full-fledged humanitarian demining market, virtually from scratch, just in 2024. According to Ihor Bezkaravaynyi, deputy minister of economy of Ukraine, there was no previous such experience in the world that Ukraine could turn to for guidance when forming the market.

"What happened in Ukraine was a precedent," Bezkaravaynyi says. "And, in fact, this is the main reason why it took nine months from the moment the decision was made that this area would be financed from the state budget to the moment of actual launch."

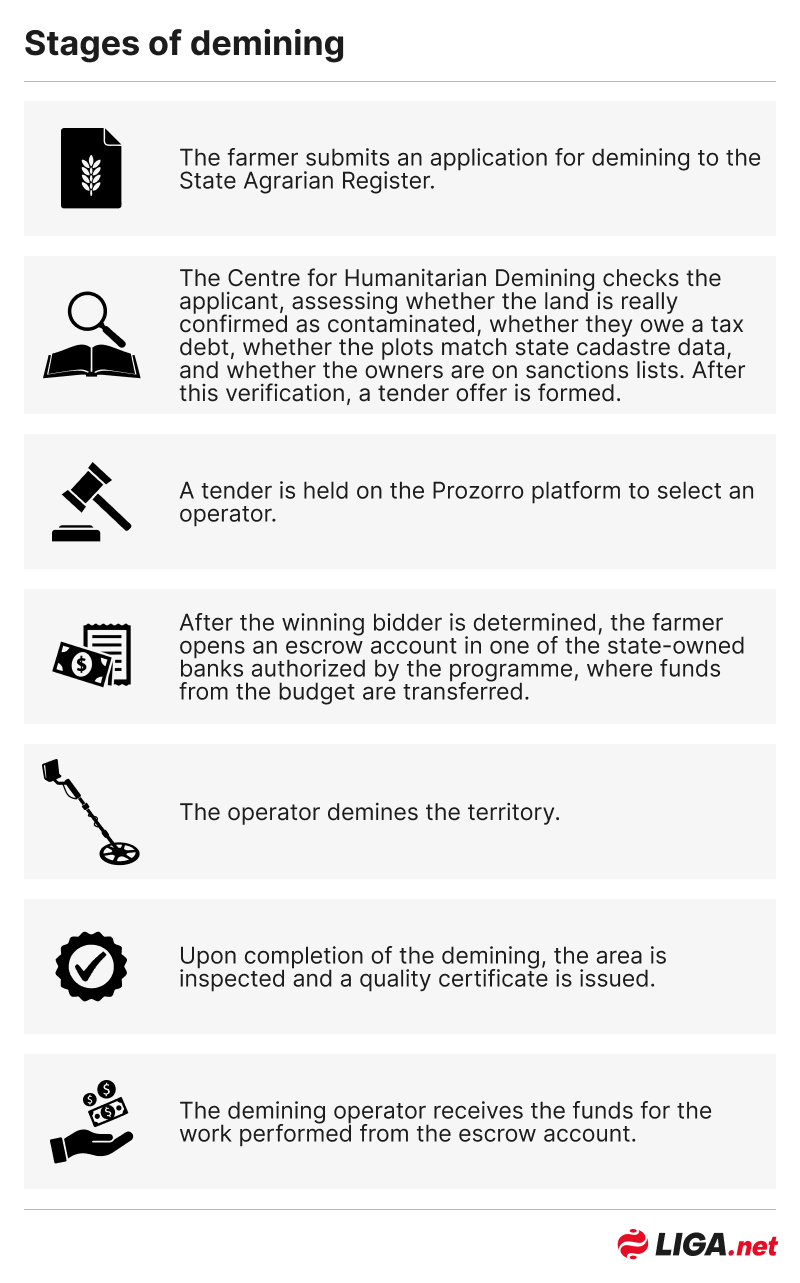

Bezkaravaynyi says the government tried, on the one hand, to build a transparent system that would be understandable, and without pitfalls, while on the other hand, it attempted to avoid delays in procedures. One of the main issues was to work out how to formalize the relationship between the service requester, which is the farmer, the provider, which is the operator, and the Centre for Humanitarian Demining.

"Another component is the duration of the process," Bezkaravaynyi explains. "Demining can take years to complete, and we’re limited by the budget year. We had to develop an algorithm to ensure that the money was saved, but neither the farmer nor the operator had access to it until the work was completed. So, we came up with a format where money from the budget is transferred to an escrow account in a bank. The funds are credited to the operator's account when the demining work is completed."

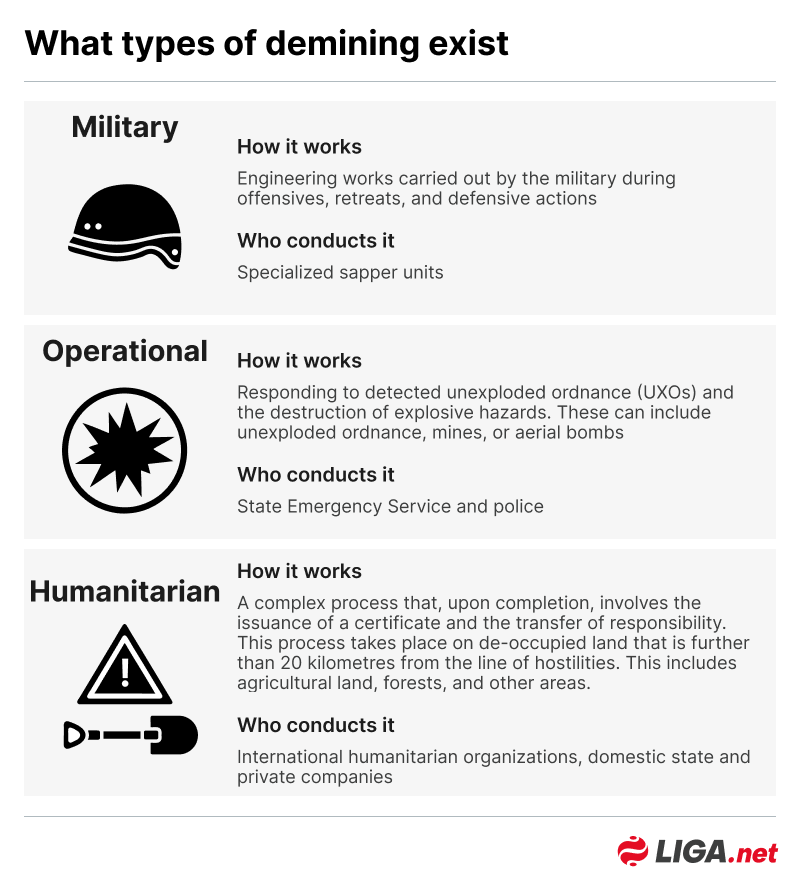

Volodymyr Baida, director of the Centre for Humanitarian Demining, notes that until 2024, humanitarian mine-clearing was not as widespread because there were not many mined areas in the world where there were no ongoing hostilities. Operational and military demining has been carried out in Ukraine since 2014. But a third component was needed to launch the humanitarian demining market: a legislative framework (created over the past two-and-a-half to three years), and market participants – demining operators, and service requesters, and solvent customers. Today, the market is supported by the state and international partners.

"Why was the market launched only this year? Because for it to function, there must be effective demand," Baida explains. "A farmer or household owner, perhaps with a few rare exceptions, won’t have enough money to clear their land of mines. That’s why we started to attract funds primarily from Western partners, donors, and various charitable organizations."

The state also joined in, and as a result, a programme was created to compensate farmers for the demining of their land. In 2024, UAH 3 billion (U.S. $71.3 million) were allocated to this programme. This is what we consider the starting point of the market," explains Baida.

According to Bezkaravaynyi, there is no sustainable and unified model for coordinating this process with the regions, and one should not be imposed, as each region has developed its own communications model.

"Each head of an oblast military administration is a local administrator who understands the local (conditions)," says Bezkaravaynyi. "They know better than anyone else how to work with this region, with these people, in these conditions," Bezkaravaynyi explains.

How the demining compensation program works and how much it costs

At the same time, when the process of creating a market began, in addition to developing the architecture of the programme itself, the issue of determining the cost of demining also arose, as it was unclear where to start. Currently, the cost of demining one hectare of agricultural land is calculated according to a special formula developed by the Ministry of Economy, which considers the degree of land contamination and operator costs.

On average, demining one hectare costs between UAH 40,000 and UAH 60,000-70,000 ($851 to $1,426-1,663). Bidding for the work is conducted through the Prozorro platform. As of the beginning of December 2024, 191 applications from farmers for demining had been submitted, and 51 auctions were held.

"Some of the applications did not pass the verification – the territories had either already been cleared or no mines were observed there," says Baida. "There were companies that did not meet the requirements – for example, they had a large tax debt – or companies whose owners were on sanctions lists. Sometimes the plots do not match the cadastral numbers, as it’s common for farmers to exchange plots. So there are a number of reasons why an auction might not be conducted."

Demining operators are in short supply

Over the year, the number of mine action operators in Ukraine has more than doubled, from 30 to 67 companies. The introduction of unified certification rules, approved under parliament’s Resolution 123 of 2 February 2024 "On the Implementation of a Pilot Project on the Certification of Mine Action Operators and Mine Action Processes," allowed for the rapid certification of operators. This document standardized the conformity assessment procedure for all bodies involved in operator certification.

To further simplify the certification procedure, a decision was made to introduce the electronic submission of documents through the Diia state services portal. This will cut down on bureaucratic procedures and speed up the issuance of certificates.

However, the new system will only be launched next year. Despite the growing number of operators, demand for their services remains high.

"Given the scale of explosive contamination in Ukraine, the need for mine action operators is extremely high," said Dmytro Panshyn, head of the Humanitarian Demining Department of the Ministry of Economy. "The number of operators required depends not only on the total area of contaminated territories but also on the number of demining teams, and their effectiveness. Currently, the priority is to increase the number of operators who survey areas to determine the boundaries of contamination. This will allow for more accurate planning of demining operations."

Experience of Kherson Oblast

The best demining performance in Ukraine has been seen in Kherson Oblast. According to Dmytro Yunusov, director of the Department of Agriculture and Irrigation Development of Kherson Oblast State Administration, the area of right-bank Kherson Oblast that was liberated in November 2022 is 683,000 hectares, of which about 520,000 hectares is agricultural land. Over two years, 387,000 hectares have been demined.

The plan was to clear 247,000 hectares by the beginning of 2024. That goal has already been exceeded, with 248,000 hectares now cleared of mines. According to Yunusov, the good results were achieved due to the clear coordination of all participants in the process.

"We’ve established a demining coordination headquarters at the Kherson Oblast Military Administration," he says. "The headquarters is headed by a representative of the Ministry of Defence, Oleksandr Shchebetiuk. In addition to the farmers themselves applying for demining, the heads of the military administration of each community were also appointed to be responsible officials. The main task is to demine the land that was officially used, and from which taxes were paid to the budget, and to make it be ready to be cultivated immediately. Thanks to this, more than 80% of the demined land is already in use."

The specific features of the region include the presence of irrigation systems, which make demining land plots much more difficult. Before the full-scale invasion, Kherson Oblast had the largest area of irrigation systems in the country, at 427,000 hectares.

"The occupiers set up their positions in the canals and made passages and fortifications," Yunusov says. "This makes it very difficult and dangerous to carry out demining there. In addition, the canals are overgrown with reeds that do not burn. Nevertheless, 90% of the canals on the right bank have already been cleared of mines."

The region has ambitious goals for 2025: By summer, it plans to demine everything except the riverbank strip of the Dnipro River.

"We’re also preparing to demine the land on the left bank – we need to survey one million hectares there in one year," Yunusov says.

Results and international support

nternational support has played a significant role in achieving these outstanding results. Among Ukraine's key and strategic partners are the United States, Switzerland, the European Union, Japan, the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, Germany, Norway, Canada, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, France, the United Kingdom, and other countries.

According to Yevheniia Bodnia, head of International Coordination and Financing at the Mine Action Office, the assistance of international partners in demining has been unprecedented.

"Overall, the global demining budget before the full-scale war in Ukraine was approximately $500-600 million per year," Bodnia says. "We’ve now raised more than $1 billion since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. However, we need to understand that this scale of assistance will not be with us forever, which is why we are thinking about long-term, sustainable, and innovative financing instruments involving the capital market and the private sector."

Funds provided by international partners come in various forms. A portion of the funds – about 30% – goes directly to international demining operators to carry out demining operations. Another part – about 32% – is used to increase the capacity of Ukrainian state institutions through the development of training centres, and training deminers, while up to 20% is spent on the purchase of machinery and equipment that is transferred to Ukrainian state institutions. The rest is spent on mine risk education, assistance to mine victims, and other needs.

"International partners support a wide range of mine action initiatives in Ukraine," says Bodnia. "This can include both basic research and development of new technologies, as well as the creation of specific projects, such as training centres. Often, international partners allocate funds for the large projects of international organizations, with which we actively cooperate to effectively channel funding for project management to meet the needs of the sector."

For 2025, the ministry's priorities are to attract funding for the work of domestic demining operators, which can now work through the compensation programme, and to strengthen the capacity of the sector. It also plans to develop an automated system that will prioritize demining. In addition, the ministry is working to promote demining equipment produced by Ukrainian manufacturers as part of the "Made in Ukraine" initiative.

Over the past three decades, UNDP and its partners have worked in more than 50 countries to help them address the challenges of landmines and other explosive hazards.

In Ukraine, UNDP supports the government in all areas of humanitarian mine action: Coordinating the humanitarian response and international support for mine action; advising on the preparation and implementation of national strategies and standards; and facilitating safe returns, reconstruction, and recovery through the provision of technical assistance, expertise, and specialized equipment.

In addition, UNDP seeks to improve life-saving emergency medical care, ongoing rehabilitation, and mental health and psychosocial assistance, enabling landmine survivors to receive social and economic support to continue to lead full and dignified lives.

The UNDP mine action project is supported by the European Union, and the governments of Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, the Republic of Korea, the Republic of Croatia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Credits: UNDP in Ukraine

Comments (0)